If the Supply of Lambs Hold Out: Simen Johan’s Until the Kingdom Comes

Originally published on Lay Flat, December 2014, ed. Shane Lavalette

Coinciding with his 2013, exhibition of the same name, Simen Johan released a book of his work, Until the Kingdom Comes. The 12.5x15.5” book contains twenty-eight photographs spread over sixty-four pages. The pages are unbound. Even on a table, this results in a bit of slippage when paging through the book. Photos are often split across a spread and must be regularly realigned. The book is always falling apart, much as many of the environments depicted inside seem to be disassembling. This conceptual hook sets a bit weakly in the face of material realities. The paper is a smooth matte surface of 100% recycled post-consumer waste material. This material sourcing is a counterweight to the environmental desolation that permeates many of the images. The cover photograph Untitled #171, depicts over sixty small Yellow-headed Blackbirds populating, and even nesting in, a burnt black landscape with sludge covered ground – little avian bits of color and life in the face of devastation. The matte surface of the paper dulls the blacks and the depth of the images a bit more than one might hope. Given that the cover of the book bears no distinction from the interior pages, other than being the outermost sheet, it feels redundant to see this image a second time inside. While the material attributes of the book leave some things to be desired, the work itself and the sequenced compilation of it into this loose folio present the viewer with dramatic images containing rich and complex thought.

In the 2011 press release for Johan’s Until the Kingdom Comes exhibition at Yossi Milo Gallery, Johan states that the work, while having Biblical allusions, “refers less to religious or natural kingdoms and more to the human fantasy that one day, in some way, life will come to a blissful resolution. …In a reality where understanding is not finite and in all probability never will be, I depict ‘living’ as an emotion-fueled experience, engulfed in uncertainty, desire and illusion.”[1]

It is a curious move to invoke a particular bit of language and thereby the concepts that come with it, and then try to distance oneself from it. In this case, the point of such an act, presumably to guide the viewer away from limiting the pieces to religious commentary, does not keep the title from bringing the richness of the eschatology he references to bear on his photographs. And, it certainly does not diminish the way in which they carry meaning.

The project’s title derives from a portion of what is commonly known as The Lord’s Prayer, where Jesus prays “Thy kingdom, come, thy will be done, on earth as it is in Heaven.”[2] This bit of the prayer refers to an expectation and desire for a future condition that returns the earth to something akin to what was lost in the expulsion from the Garden of Eden – a state of peaceful bliss and coexistence between god, humanity, and nature. Johan brings the Eden narrative to mind with his photo of a tangle of python silhouettes writhing around a branch, devouring innocent mice and striking out at flitting doves, suggesting both the narrative instigator of the troubles of humanity, as well as the struggles that continue to plague their resolution.

Biblical and theological relationships iterate from this in a tangle of history and interpretation that lies beyond the scope of this writing. However, one other text bears heavily upon what is seen in Johan’s photographs. Generally, interpreted to be speaking of an idyllic future, the verse, “The wolf shall dwell with the lamb, and the leopard shall lie down with the kid, and the calf and the lion and the fatling together,” comes from the prophet Isaiah. It is commonly elided into the phrase “the lion shall lie down with the lamb.”[3] Given Johan’s subjects in the photographs, which include both wolf and lamb, though not in the same photo, the resonance of this text is pitched.

The rich literary and visual history of these themes and metaphors progresses through the centuries. An incarnation of these ideas along the path to Johan’s photographs is P.T. Barnum’s exhibition The Happy Family. One of Barnum’s most popular and profitable attractions was The Happy Family. According to an often quoted anecdote, it originally consisted of a cage holding a lion, a tiger, a panther - and a baby lamb. When questioned about the future of The Happy Family, Barnum quipped, "The display will become a permanent feature, if the supply of lambs holds out."

The glory of the much-lauded original exhibit had deteriorated by the time Mark Twain paid it a visit:

A poor, spiritless old bear - sixteen monkeys - half a dozen sorrowful raccoons - two mangy puppies - two unhappy rabbits - and two meek Tom cats, that have had half the hair snatched out of them by the monkeys, compose the Happy Family - and certainly it was the most subjugated-looking party I ever saw. The entire Happy Family is bossed and bullied by a monkey that any one of the victims could whip, only that they lack the courage to try it. He grabs a Tom by the nape of the neck and bounces him on the ground, he cuffs the rabbits and the coons, and snatches his own tribe from end to end of the cage by the tail. When the dinner-tub is brought in, he gets boldly into it and the other members of the family sit patiently around till his hunger is satisfied or steal a morsel and get bored heels over head for it. The world is full of families as happy as that. The boss monkey has even proceeded so far as to nip the tail short off of one of his brethren, and now half the pleasures of the poor devil's life are denied him, because he hain't got anything to hang by. It almost moves one to tears to see that bob-tailed monkey work his stump and try to grab a beam with it that is a yard away. And when his stump naturally misses fire and he falls, none but the heartless can laugh. Why cannot he become a philosopher? Why cannot he console himself with the reflection that tails are but a delusion and a vanity at best?[4]

While, it is this later state of The Happy Family that echoes the faltering and unrealized eschatology of the sloughy creatures that proliferate Until the Kingdom Comes, not all of Johan’s animals appear to wait in defeat. Some instead, suggest the veneer of plenty and peace that comes from Barnum’s duplicitous lamb replenishment strategy. A number of Cotton Headed Tamarins and tiny snails greedily devour an overabundance of pomegranates in paradisiacal proportions. But, lest this kind of communal fruit eating make the wrong suggestion about the dietary proclivities of Johan’s beasts, in another photo, a White-crested Hornbill rests guardedly on a broken branch, with the hindquarters of a frog dangling from its beak.

Johan’s lamb is faring better than Barnum’s renewable sheep. The photo of the lamb is as peaceful as one might expect. The grassy field recedes to a misty horizon, with tree braches vignetting the top corners of the photo. Under the shade of the tree, the lamb appears to have just risen from rest to a sitting position. It looks tranquilly at the camera. The wolves, however, bear a more direct kinship to the version of the peaceable kingdom that Twain saw in Barnum’s exhibit. One sits; others prowl behind. Their fur is matted and their bodies gaunt. They appear unable to move effectively, bogged down by their unnaturally sea-swamp habitat. These wolves are desperate for a lamb.

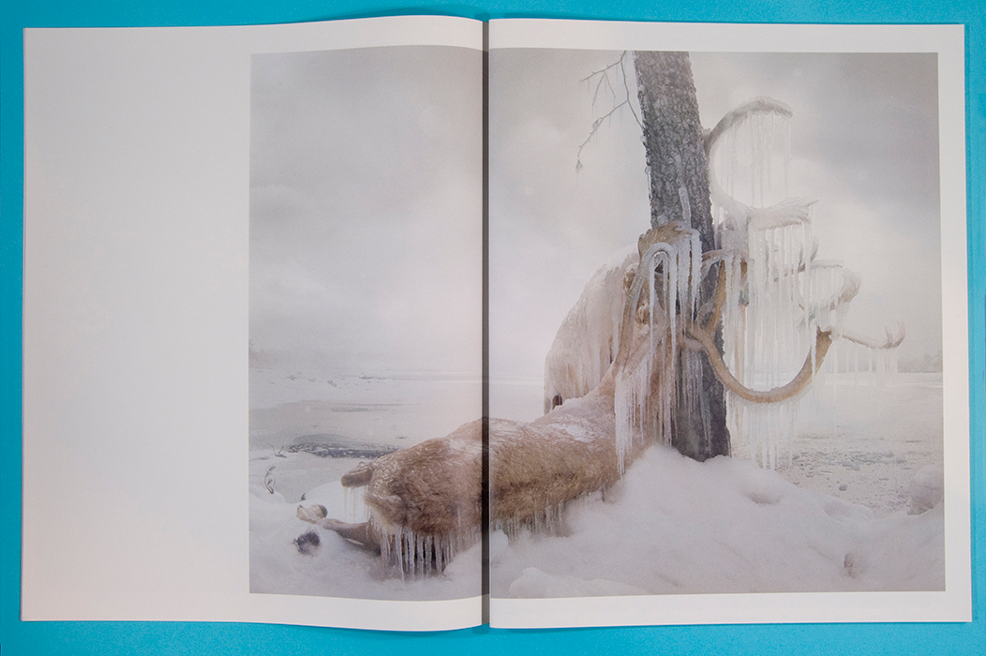

The animals in the photographs are totemic, representing something beyond themselves. While often photographed in species isolation, they do not read as specimens. Whether engaged in combat or encased in ice, the beasts are integrally connected to their environments, though they remain monumental within them. They are as sculptural as the physical objects that often accompany the photos in exhibition. They embody the spiritual state of both expectation and defeat, the cracks in the hope for the future that run through human desire.

The anthropomorphized nature of the animals in the photos easily transfers the emotional condition of the image from the animal kingdom to human psychology. Johan’s flamingos have a quality of animated entanglement reminiscent of the flamingo croquet mallets of Disney’s Alice in Wonderland. A lemur reclines in a tree branch, a bit of a dandy. It has picked a hibiscus and draws it to its nose, savoring the aroma. Two snowy owls sit on a park table in the fog, one cranes his neck in a hoot that becomes a jolly chuckle. A jungle of red monkeys stare cautiously at the viewer. One, sitting towards the back, screeches at the intrusion – Twain’s boss-monkey asserting his power.

The title, Until the Kingdom Comes, and its liturgical origins fundamentally engage the idea of waiting – expectant waiting. The nature of what one does during this period of waiting is at the heart of religious and universal human experience. Johan’s totemic creatures mark this time in telling ways.

What does waiting represent in relation to (false) expectations and the realities that these icons inhabit? The multiplicity of animal responses to this seem to differentiate themselves along the lines of potential human response. The orangutan is settled on a bedding of burlap sack on the forest floor among the roots of a large tree. Gravity weighs heavily on his jowly face, as he looks sadly into the distance. The light reflecting in his eyes suggests expectation, awaiting the movement of the sun that is breaking through the canopy. An albino deer moves confidently through the snow-covered forest, its abnormal pigmentation expands its freedoms and sense of security. The bison lies in a barren waste-filled landscape, having accepted a defeat that has seemed inevitable to it in the past. It has taken the dust of the land upon itself and become a monochromatic unity under the dark skies of the approaching storm. Similarly, the rhinoceros appears to have given up, dropping into the yellow sand that dusts its own body, with no intention of ever rising again.

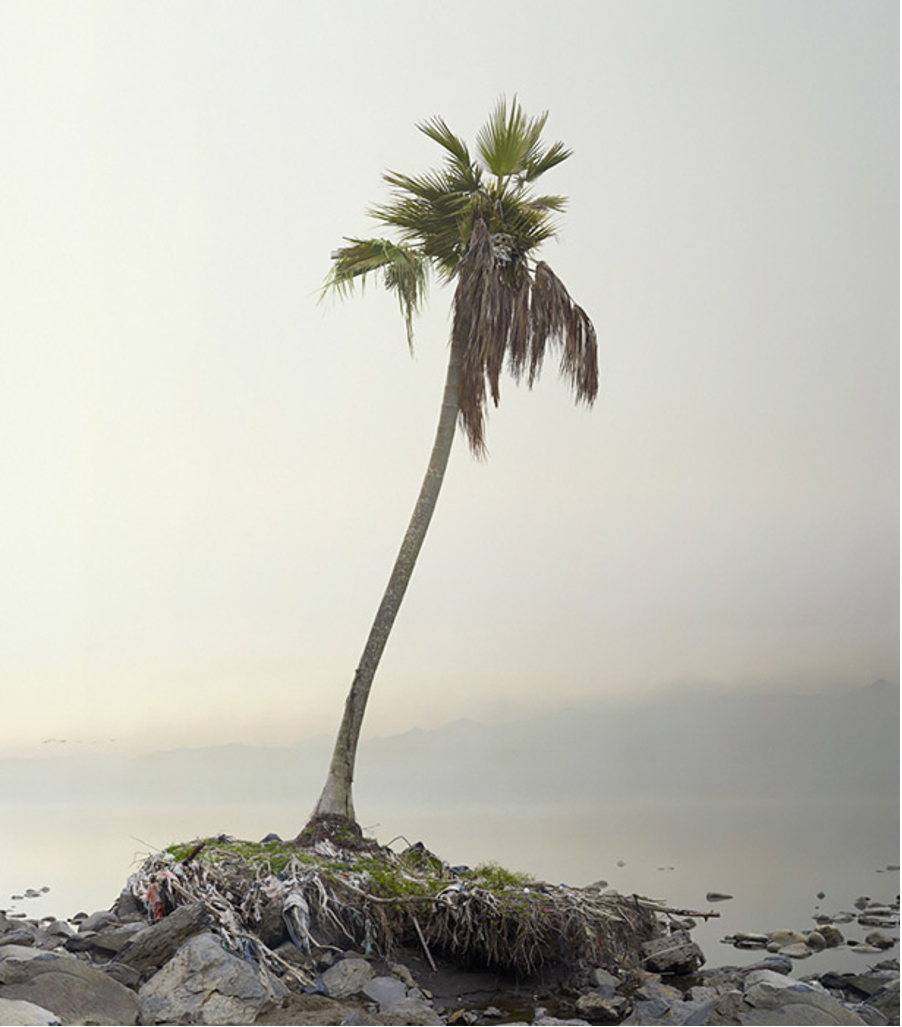

Interspersed with the fauna images in Johan’s book are a number of other types of photographs. In the position of what would be the book’s endsheets, are printed simulations of marbled paper. The swirls of color set the palette for the book while being prescient of the polluted liquid surfaces in the book. The first photograph is the entrance to a cave, where white light radiates out from the threshold, suggesting conventional passage into something transcendent. The next photograph maintains the unearthly presence, a tree deep in the fog. The first animal to appear is a similarly shrouded beast, what appears to be a hippopotamus, swimming deep below the surface, only its rump illuminated by the light from above. Then the giraffes reach their necks high into the clouds above, but this is where things begin to turn. The soggy ground is less than inviting and the mist around their heads looks as much like smog as like clouds. Any doubt about the atmosphere that is developing in this image are then removed by the subsequent photo, where two albino elk, antlers locked around a tree, lay on the ground in defeat, fully encased in a cocoon of ice. Johan pulls us back and forth between these two ideals through the sequence of the book. A palm tree serves as a symbol of paradise, but it appears without ground, roots exposed, washed up on the edge of a rocky shore. A mountainscape is covered in a dense mysterious fog that becomes magical as the light passing prismatically through the droplets of moisture creates a rainbow filter over the gloom.

The amalgamation of sentiments, creatures and environments suggests the kind of universal harmonious union that is referenced by the title, but in the places where these elements are most readily apparent, Johan disintegrates the Happy Family. Parakeets flutter around in agitation as a moose inflicts yet another wound about its own kind. This building of potential for something transcendently concordant to be torn asunder by its own unsustainability is at the heart of Johan’s assessment of our existence. The book concludes with two foxes, huddled together in the snow. Their snouts matted with blood, tears freezing down their faces. Despite moments of hope and inklings toward something different, these creatures can barely hold it together. While the same thing could be said about the binding of the book, the photographs inside are insightful and incisive. They leave one fearful that the philosopher monkey is correct and our tails/tales might be “a delusion and a vanity at best.”[5]