100 Artists See God - A Review

Originally published in Religion and the Arts, Vol. 8, No. 4, ed. Dennis Taylor (Boston, MA: Brill 2004).

Far too often, religiously themed exhibitions result in a fine collection of pious, sentimental, and modestly crafted pieces brought together for a festival of religious and artistic mediocrity. It is right to approach such events with cautious skepticism. But, with regards to 100 Artists See God, it is worth swallowing that initial swelling of pretense in order to experience the varied strengths of the works included.

This exhibition opened in the spring of 2004 at San Francisco’s Contemporary Jewish Museum. The show is traveling nationally over the next two years, and is also available as a print catalogue. Sponsored by Independent Curators International (ICI), art world veterans John Baldessari and Meg Cranston have assembled a rare confluence of artists dealing with subject matter that is typically shied away from in contemporary galleries. But as the curators point out, the world is profoundly influenced by concepts of God, concepts held by believers and unbelievers alike, and especially in our current political climate. As Baldessasri describes in the pitch for the show, “God is news.” (100 Artists, 6)[1] With this in mind, the show asks a natural question: as voices of expression in our culture, what do artists have to say about God? The answer is a mixture of the irreverent, irrelevant, silly, serious, pious, considered, and possibly revelatory.

Just over a hundred artists were approached and asked to create new work, or submit existing work, in response to the theme “artists see God.” The curators were quite clear that this was about representing God, not about their own belief. And so, the artists were chosen not according to their own faiths or lack thereof, but because the curators knew and respected their work.

Many of the people involved have impressive résumés: Chris Burden, Andreas Gursky, Damien Hirst, Roy Lichtenstein, Paul McCarthy, Gerhard Richter, and Ed Ruscha. The list of over one hundred artists is filled with quite a few recognizable names. Interestingly enough, a great many of the prominent artists who often use religious iconography are absent: Andreas Serrano, Robert Gober, Bill Viola, to name a few. While a single art show cannot be all-inclusive, one does suspect that there may have been some attempt to draw representations of God from people who are not likely to offer them up on their own. While denying that any conscious attempt was made in this direction, Baldessari did confess that such a motive was implicit in the request made of the artists. “It was a bit like fishing…to see if they would take the bait.” (Baldessari, 6 Aug.)[2] Maybe it takes something like this to get these artists to speak on this touchy and unfashionable subject.

Before examining the particular works in the show, there is one more curatorial issue to be addressed. Alongside each of the images, in an unfortunately large font on the wall label, is a category to which each piece has been assigned. They follow a set form, “Artists see God as ___________,” with the blanks filled in with such categories as Architect, Everywhere, Ineffable, Light, Love, Tyrant, and the Extraordinary Force of Nature. It is nearly impossible to look at the works without these categories looming large. Baldessari confided that neither he nor Cranston wanted to pigeon hole the work, but ICI and the exhibiting venues requested this parsing of the exhibit. (Baldessari, 6 Aug.)[3] Purportedly these groupings are there for the benefit of the viewer, to help them grapple with and assimilate the work. But the categorization does little more than spoil it. And, even more dumbfoundingly, some of the works do not seem to make any real sense in relation to their assigned category. Must it be that the devout are too dull to understand art, and the artistically erudite are too heathen to understand the transcendent? In the catalogue, these categories appear as chapter headings, and are slightly less invasive. After turning the page of the chapter introduction, the reader no longer has to be reminded of the ways in which she is asked to classify the pieces. Even if the categorization was done with the best of intentions, it is insulting, and has a nasty tendency to force or limit interpretations of the works. The heavy hand of the curator should have left more to the subtler hand of the creator and the discerning eye of the viewer.

If we manage to look past the labels, we see very little work that borders on the pious and sentimental. Although a couple of pieces do tread lightly into that territory, even if only to defuse it. Simon Patterson’s Landskip (2000), where shafts of light filter through trees and colored mist that turns out to be an army gas grenade test, is a good example of this. There are also works that, quite frankly, appear to have been chosen as a random response to the theme of the show, exhibiting no coherent relationship to “seeing God.” Some of these seemingly desultory works can be better understood by reading the artist statements, but these statements are only found in the catalogue, and are not present in the exhibition. The most common revelation is that the work is an allusion to some sort of pantheism or panentheism. While these expressions are likely genuine, they are not particularly innovative, as in the case of Chris Burden and James Welling’s photos of their dogs. And more tragically, they are not compelling representations of the ideas they convey.

The painting Gray (Grau) (1973) by Gerhard Richter is characteristic of two prominent types of work shown by artists in the exhibition. It is gray. Richter says, “A monochrome gray painting, oil on canvas, in any common size, is simply the only possible representation/image of God. That is obviously very simple, too simple; of course when I made this gray painting I neither intended to express a conception of God nor would I be able to make such a painting.” (100 Artists, 56)[4]

One of the obvious characteristics of this work, and many others, is its intention. As one studies the collection, it is clear that a great many of the works were not “intended” for this context at their inception. Andreas Gursky’s Love Parade (2001), an aerial panoramic photo of the massive crowd gathered at a park festival, comes to mind. The artwork has been repurposed and reinterpreted for this exhibit. In cases such as the Gursky photo, this adds a new layer of meaning. In others, such as Roy Liechtenstein’s Mirror #8 (1972), which is a screenprint of two mirrors made in his signature style of enlarged Benday dots, this recontextualization feels forced and even confused. For whatever reason, each artist has contributed their piece and presented it as a vision of God. But in some instances, it seems that the artists did not look too hard or too carefully for God.

The Richter painting is also characteristic of the form of other works in the show. Several artists present solid color minimal works or some variety of non-representational abstraction that find their spirituality and reference to the divine in their ineffability and openendedness. It is somewhat disheartening to see these types of work in a show that otherwise feels contemporary. The disinterested contemplation of abstract works, either as a secular surrogate for religion or fundamentally akin to religious practices and goals, feels as though it has long been played out. Clement Greenberg and Harold Rosenberg worked out these ideas, and they were brought to a pinnacle in the Rothko Chapel. There is little or nothing added to our understanding of art or artists perceptions of God by perpetuating these kinds of art in these kinds of contexts.

This is not to say that exploration of religion and art’s commonalities: shared or similar experiences, goals, and ways of operating is now fruitless. By no means! It does, however, demand that artists do this in ways that bring something fresh to the table. Religious and artistic traditions and practice continue to intersect in their drives, concerns, and relationships, both in historical and contemporary practice. New congruencies join historical overlaps and beg for current address. The following four pieces from the exhibition engage the intersections of these arenas in a contemporary fashion.

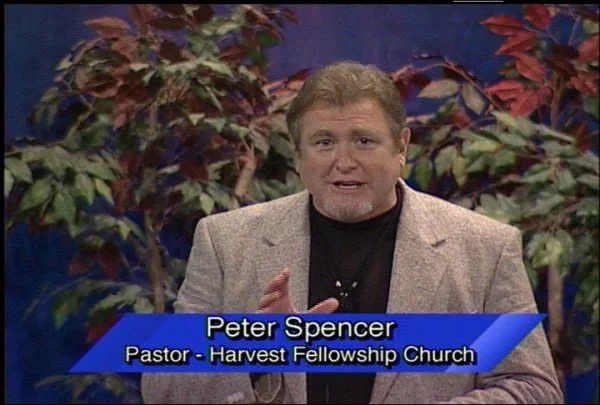

Christian Jankowski complexifies the association of art and religion in his fifteen-minute video, The Holy Artwork (2001). We are presented with a charismatic worship service at Harvest Fellowship Church. The artist, who emerges from the congregation with camera in hand, comes onto the stage and collapses on the ground at the pastor’s feet. While this might appear as if the artist has been slain or crushed with the hands of religion, it is not that simple a signifier. In the context of this charismatic style worship service it is not uncommon for parishioners to fall to the ground, or be “slain in the Spirit”, by the power of God. Rather than death, this physical reaction represents a coming of the divine to the individual. It is a sort of commingling between Creator and Creation. As described by the pastor in the video, Jankaowski’s falling is an emptying of himself to allow others, the audience, to participate in the artwork.

The service continues with a short sermon by Pastor Peter Spencer about contemporary art bridging the gap of art, religion, and television. Spencer’s sermon uses the language of both art and religion, moving back and forth between the creation of the world and the creation of art. The world and art together become The Holy Artwork, slipping easily and unknowingly between each other. Art becomes a collaborative work between creator and viewer, in both the realm of the divine and the human. Jankowski remains prone as the Praise Band steps around him to sing a chorus. At the end, the Pastor says a prayer, and Jankowski rises, thanking God for making this possible. The familiar comparison of artist to God, and of art to religion, is given a facelift with televangelism and contemporary praise and worship songs. More importantly, though, Jankowski’s collaboration with an evangelical pastor to create the piece allows for a rare level of commingling between the religious practitioner and the artist. Typically the words of critics brought these two worlds together. Now Jankowski joins them in the practice of creation and does so in the immediate context of a Christian worship service. Humorous and prodding, The Holy Artwork plays pleasantly with language and with the role of creation and creator in a form that, from its inception, brings the two worlds together.

Christian Jankowski, The Holy Artwork, 2001, DVD, 15 minutes 47 seconds, Collection of the artist. Courtesy Maccarone Inc., New York. Commissioned by ArtPace, San Antonio

Another way to strengthen the relationship of religion and art is by identifying their common concerns. Veronica’s Veil has a rich presence in religious artwork. To some, it is one of the earliest representations of Christ, and so one might expect it to persist in contemporary work. Jeffrey Vallance’s Relics From Two Vatican Performances (1992) has become a part of this history. While on pilgrimage in Rome, Vallance approximated the process of the original veil’s creation. He splashed espresso on his face and then pressed his face into a silk handkerchief. The coffee-stained cloth is presented to us in matt and frame. Vallance gives us the relic of his performance, just as Veronica gave us the relic of the act of Christ. With some performance work, all that is left is an artifact or documentation of the piece’s occurrence, with the rest of the piece having passed into the ephemera. This is true for Vallance’s re-enactment of the sixth station of the cross. In the performance, he presents a familiar equation relating art to religion, suffering, and redemption. The artistic act has become hallowed and sacred. Yet, it stands apart from most instances of this concept. The coffee-stained cloth brings into play the notion of the potency of the act remembered by the remaining artifact – an issue in the art world with regards to the nature of documentation of performance works, and in the religious world with regard to relics and sacraments. This dimension is a welcome addition to a well-worn discussion. However, it may become more difficult to take seriously the liturgical and sacramental implications of the work when the blood of Christ becomes a double espresso, but, then again, perhaps no less so than when it is Welch’s grape juice in a plastic shot glass.

Still lingering in the territory of the Passion is Paul Pfeiffer’s Fragments of a Crucifixion (After Francis Bacon) (1999). Projected closely against the wall, so that the image size is only a few inches high, Fragments of a Crucifixion is a short video loop of a lone basketball player, dressed in a white uniform, screaming in apparent torment while flash bulbs ripple through the crowded stands. Other players, team names, numbers, and logos have been digitally eliminated from the frame, so the figure stands alone, mouth open and arms tense, in an expression of anguish. The short duration of the video, which is only a few seconds, traps the player in the scream, and in the spectacle that he has become. It is unclear why he cries out, but it exudes anger. The work certainly has ramifications in a number of arenas, but in this context we are asked to bring it straight home to its title. We are asked to look at the reference to Bacon’s screaming pope, another spectacle in his bulletproof bubble, and to the display of the Crucifixion itself. The spectacle, isolation, and eternal Sisyphusian sense of the work make the video writhe with contortions of pain. Seeing the loop of pain, begs the question of purpose and authenticity of the suffering. Pfeiffer has made a multimillion dollar job seem void and meaningless. Is this the price of fame? Is isolation amidst a crowd the tradeoff for a star’s messianic status? If so, this might be something hypothesized for Jesus as well. And, more importantly, is there something redemptive in this basketball pain? Pfeiffer implies nothing more than emptiness and repeatedly relived affliction – a truly fragmented Crucifixion. The use of the language of the Cross in the work offers more cultural indictment than religious insight. But, one could also argue that, from the beginning, the Cross was cultural indictment as well.

Paul Pfeiffer, Fragment of a Crucifixion (After Francis Bacon), 1999, DVD and Sony CPJ200 projector, Courtesy the artist and The Project, New York

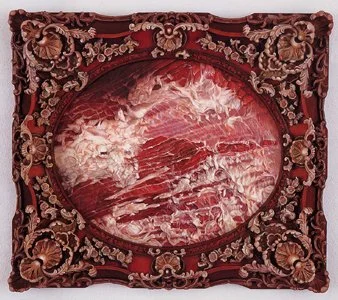

One of the more decorous and grossly beefy works in the show, Victoria Reynolds’s For the Carnal in Dante’s Hell (1999). The painting appears as a roof of red flesh with the pink and white tears of insulating fat hanging from the beams of muscular fibers. The detail and realism of the image are sublime in the transformation of the freshly cut meat into a transcendent ceilingscape. The corpulent painting is evenly matched with its opulent framing. Chromatically the same, the frame is ornamental to excess and as lush as the bloody flesh that Reynolds has bequeathed to Dante’s Carnal. Having given into the flesh in life, the Carnal are offered flesh in death. Is this flesh the light of God and reason that Dante says the Carnal so desperately need? Christian rituals of Eucharist might say, yes. Reynolds offers a visceral and bloody reality that is beautified and given a sense of abundant luxury in both its framing and rendering. The qualities of the painting and the association with the text of The Inferno provide a considered and substantial reflection of the portrayal of the flesh in regard to both sin and redemption.

Victoria Reynolds, For the Carnal in Dante’s Hell, 1999, Oil on panel in artist’s frame, Framed: 28 1/4 x 32 1/4 in. (71.8 x 81.9 cm), Collection of the artist

In this show, slightly more prevalent than work addressing the commonalities of art and religion is the sarcastic work. Given how the art world regards religion, it is not surprising that many of the works in the show are delivered with tongue planted firmly in cheek. While the dripping sarcasm and irony of contemporary art is not limited to religious subject matter, it does find a ready target there. Thankfully, the works are often clever and well executed, thereby engaging the audience in a way that entertains and provokes. What may come as a bit of a shock is how often the work transcends the gag and provides some genuine insight.

Terry Allen’s Jesus (upside down and backwards) (1993) is just such a work. At first glance the sign, scripted in blue neon, does not read right – familiar but incorrect. The title instructs. In one’s mind’s eye, the viewer must rotate the neon around. Flip it over. “Elvis.” Elvis? Jesus? Jesus upside down and backwards becomes Elvis. Or, Elvis, when turned and spun around, becomes the Christ. Certainly a large portion of Americans behave as if this might be true. Pilgrimages to Graceland receive as much reverence as those to the Promised Land. In the words the artist, “The only difference I can see in how the culture regards ELVIS son of Vernon and Jesus son of God is, to my knowledge, JESUS never recorded anything called ‘DO THE CLAM.’” (100 Artists, 88)[5] He has made a simply play, and one that has been made before, but one we can still enjoy. The salvific power bequeathed to celebrity and popular culture is a familiar theme, but when expressed well, it can refresh the notion in our consciousness without seeming to be old news. It is even more satisfying when one pays too much attention to the wall label and notices that this piece is on loan from the collection of David Byrne, a rock music icon and conceptual artist most famous as the front man for the Talking Heads.

Terry Allen, Jesus (upside down backwards), 1993, Neon, 4 x 12 in. (10.2 x 30.5 cm), Collection of David Byrne and Adelle Lutz

Walking under the King, through the doorway, three fish lay still, possibly dead, on the floor mat of a car. Cast in bronze, they are painted blue, green, and orange with what is distinctively automotive paint. The fish look as if they have just flipped their last flop. Jonathan Furmanski has branded each of his Bumper Fish (2002) with an automobile logo: Nissan, Ford, and Honda. He provides us with a clever inversion of the prevalent bumper symbol war. This little battle was begun by the application of the ancient Christian symbol of the Ichthus, a simple outline of a fish that encompasses the Greek letters for the word “fish” which doubles as an acronym for “Jesus Christ, of God, the Son, the Savior”, to the back ends of cars and trucks. A prevalent smart mouthed reply was soon to follow. The inside text was replaced with “Darwin” and the little fish sprouted legs. Evolutionists took their stand and, now, numerous variations of these icons exist. Through Furmanski’s work, the creation-evolution debate that has raged publicly through automobile appliqués has been called out in the absurdity of its form, if not the shallowness of the discussion itself. These floundering fish each trumpet their own brand loyalty through corporate symbology. Furmanski, pointedly reduces this volatile subject to the level of the classic Ford vs. Chevy debate – a point those involved in the creation-evolution controversy would do well to consider.

Jonathan Furmanski, Bumper Fish, 2002, Cast bronze, metal, automobile paint, and floor mat, 3 x 16 1/2 x 25 in. (7.6 x 41.9 x 63.5 cm), Collection of the artist

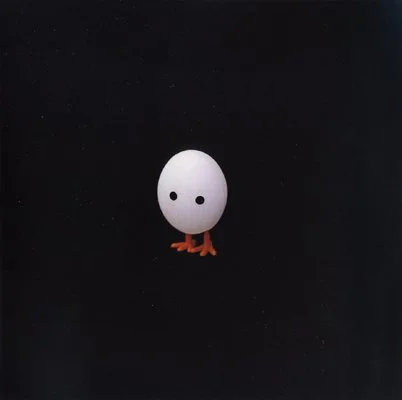

In another instance of the comic character motif, an egg with small plastic orange chicken feet and two black dots for eyes floats in the center of an oversized black field, making up Luciano Perna’s God Luck! (2002). The piece is cute in a Sanrio “Hello Kitty” sort of way, a touch unsettling due to the black, but otherwise unremarkable. The egg is surely a loaded symbol for new birth, fertility, and the like, but here is seems more that the little chicken-footed-egg is an absurdist picturing of God. It is possibly a visual tossing up of one’s hands at the nature of such a request. The point of interest arises from Perna’s artist statement in the catalogue. His explanation becomes a more compelling performance/experiment than the image. It betrays common contemporary understandings of how God is supposed to behave, with the cynical assurance that God will fail to behave at all. Perna writes:

I asked God to help me write a statement for this catalogue by guiding my fingertips over the computer keyboard. I closed my eyes, let go, and this is what came out: nklxnonx’fk n4po4po9imc[‘23\r0mcri4jjo4hcgm00it-00iiu6tbl.hv lv…(100 Artists, 51)[6]

The nonsense characters continue for about twenty times the length reproduced above. Nestled in the middle of the gobbledygook, one can pick out the words “sorry, I am too busy, god luck!” In the title and in the keyboard revelation, “God” is exchanged for or equated with “good,” by way of transposition into the common well-wishing sentiment. Yet, it seems that this fortune-cookie like message must be meant ironically, as no benefit is received. In fact, the certainty of inaction is reinforced by the addition of this revelation from the digital Ouija divination. While Perna, seems to find God largely close-lipped and far too overburdened to assist in the composition of artist statements, one might wonder if maybe God has guided his fingertips in just this way to reveal our sardonic nature.

Luciano Perna, God Luck!, 2002, Digital print, 35 x 35 in. (89 x 89 cm); framed: 36 1/2 x 36 1/2 in. (92.7 x 92.7 cm), Collection of the artist

Meg Cranston remarked that part of the intrigue of the theme of this show is that “religion typically only manifests itself ironically in contemporary art. Sincerity is regarded with suspicion.” (Cranston, 6 Aug.)[7] Thankfully this show has provided us with both types of responses. It is possible to dialogue with the culture in ways that are genuine, probing, and compelling, in ways that are more layered. Such symbolic works often take a narrative form, by relating a personalized experience combined with the experience of tradition. The multidimensionality of this way of questioning provides a richness that moves into a realm of exploration reaching beyond the work itself and into a new experience. It is subtler. No bludgeoning is necessary, with either wit, idea, or religious conceptions.

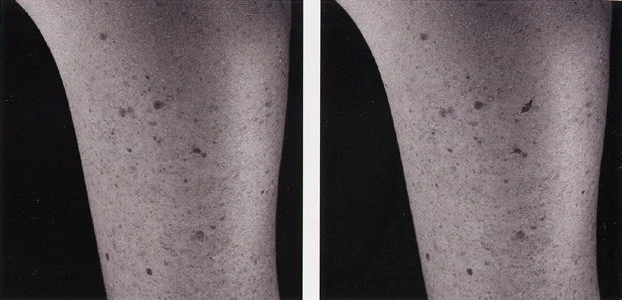

Challenging one’s own tradition is a burden for any individual, but it is certainly the responsibility of the artist. Kim Schoenstadt does this in Freckle Series: Adding Lake Nagawicka (2002). She got a freckle-sized tattoo in the shape of Lake Nagawicka, a body of water that she called home. The pair of photographs record the before and after states of her freckles. Schoenstadt has made a tiny alteration to her body that technically could prevent her from being buried in the Jewish cemetery with her family. A prohibition from Leviticus, “you shall not make gashes in your flesh for the dead, or incise any marks on yourselves” has lead to a policy at many traditional Jewish cemeteries and mortuaries that prevents burial of tattooed individuals (Tanakh, Lev. 19:28).[8] Schoenstadt’s alteration, though, is so small that it may be overlooked by those preparing her body after death. Yet, she also challenges, “We will see if g-d notices.” (100 Artists, 122).[9] Alongside this sly venture, slipping a freckle past the All-Seeing, Schoenstadt reveals an homage to Jewish tradition by dropping the vowel from “god.” This coexistence of adherence to and deviance from religion is a subtle and personal act that pits the attention and regulation of our culture against that of a god whom Schoenstadt implies is less preoccupied with such matters.

Kim Schoenstadt, Freckle Series: Adding Lake Nagawicka, 2002, Two digital prints, 10 x 10 in. (25.4 x 25.4 cm) each; framed: 14 1/4 x 13 3/4 in. (36.2 x 34.9 cm) each, Collection of the artist. Courtesy lemon sky projects + editions, Miami

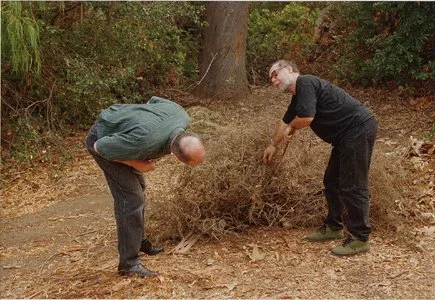

The most enchanting work of the show is an unassuming mystery. Paul McCarthy, best known for his work emphasizing the shockingly abject, proffers a single photograph of two men in the woods. One, bearded and wearing Buddy Holly glasses, lifts a pile of bush off the ground using a stick. The other, balding and holding his glasses in hand, bends at the waist to get a better look at what is being revealed under the bush. The image is well composed, engaging, and humorous in an endearing old man sort of way. In the book, McCarthy accompanies the Untitled (1998) photograph with the statement, “Looking Under Every Bush.” (100 Artists, 31)[10] Maybe, the men are searching for God, looking everywhere. The work implies a certain cynicism, since, after all, such searching must mean that God is elusive or perhaps wholly absent. But searching also suggests the hope and conviction that there is something to find. The two men look intently. The photograph delves into contemporary existential dilemmas and desires with a quiet nod to the language of tradition, invoking the symbol of the bush. What better place to look for God than in the place God first appeared to Moses? “An angel of the Lord appeared to him in a blazing fire out of a bush. He gazed, and there was the bush all aflame, yet the bush was not consumed.” (Tanakh, Exodus 3:2).[11] One can return to McCarthy’s photograph and almost hear the fellow with the stick saying, “Aaron, I’m telling you, yesterday, this thing was on fire and talking. I mean it even turned this stick I’m holding into a snake.” He pokes it to try to turn it on again, and investigates its undercarriage for some sort fire-starting of mechanism. This is an attempt to understand, to locate, to see. There is an ineffable satisfaction of discernment emanating from this work. Though one might never have guessed based on such works as The Garden, where an animatronic fellow humps a tree, Paul McCarthy has delivered astute human and theological insights in the form of a seemingly simple, quiet, and mundane image that generates far more than it uses. The bush is not consumed.

Paul McCarthy, Untitled, 1998, Chromogenic print, 20 x 29 1/4 in. (50.8 x 74.3 cm); framed: 22 x 31 1/2 in. (55.9 x 80 cm), Collection of the artist. Courtesy Hauser & Wirth, Zurich, and Luhring Augustine, New York

Cutting through the brush of 100 Artists See God, one can find artists speaking relevantly in a still, small, and alluring voice. It is a voice that addresses both culture and tradition, and, sometimes bitingly. It uses their language so that we may understand, and occasionally accesses something just a little bit mysterious in quality. It is something we cannot quite name. This virtue makes both the show and catalogue an important move of theological grappling among contemporary artists and exhibitions. Let us hope that more artists will bring us these sorts of visions of God.

100 Artists See God can be seen in its catalog form or at the following venues.

Laguna Art Museum, Laguna Beach, California, July 31 – October 3, 2004

Contemporary Art Center of Virginia, Virginia Beach, Virginia, June 9 – September 4, 2005

Albright College Freedman Art Gallery, Reading, Pennsylvania, September 19, 2005 – January 8, 2006

Cheekwood Museum of Art, Nashville, Tennessee, February 4 – April 16, 2006

For information about booking 100 Artists See God for a museum or gallery exhibition, contact ICI at (212) 254-8200 or email at info@ici-exhibitions.org.

[1] John Baldessari and Meg Cranston, curators, 100 Artists See God (New York: Independent Curators International, 2004), p.6.

[2] John Baldessari, Personal Interview, Friday, Aug. 6, 2004.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Baldessari and Cranston, 100 Artists See God, p.56.

[5] Ibid., p.88.

[6] Ibid., p.51.

[7] Meg Cranston, Personal Interview, Friday, Aug. 6, 2004.

[8] Leviticus 19:28 (JPS)

[9] Baldessari, 100 Artists See God, p.122.

[10] Ibid., p.31.

[11] Exodus 3:2 (JPS)